Episode Transcript

AB20030503_HistoryOfBuddhism

Summary

The Buddha taught that meditation is a way to gain Insight into the nature of our mind and to overcome our sufferings. Buddhism is a tolerant religion that has never fought a war in its name. When Buddhism spread, it created three great traditions which have a lot of similarities. Practices and customs vary significantly among Buddhist traditions, but the teachings are fundamentally the same. Buddhism developed organically and each community depended upon its own goodness.. The Buddha's awakening came about through his experiences in a previous life and his practice of contemplation under a tree, leading him to understand the nature of the world himself. In Buddhism, enlightenment is happiness, and the only way to achieve it is to practice meditation and live a simple life dedicated to the true realization of truth. The history of Buddhism starts 2600 years ago with the birth of the person who became our present Buddha. Buddhism is based upon teachings such as reincarnation and the law of karma. After the Buddha died, his teachings were organized and memorized by monks in order to be passed down and conserved. The Buddha's teachings still have a deep meaning to Buddhists today.

Transcription

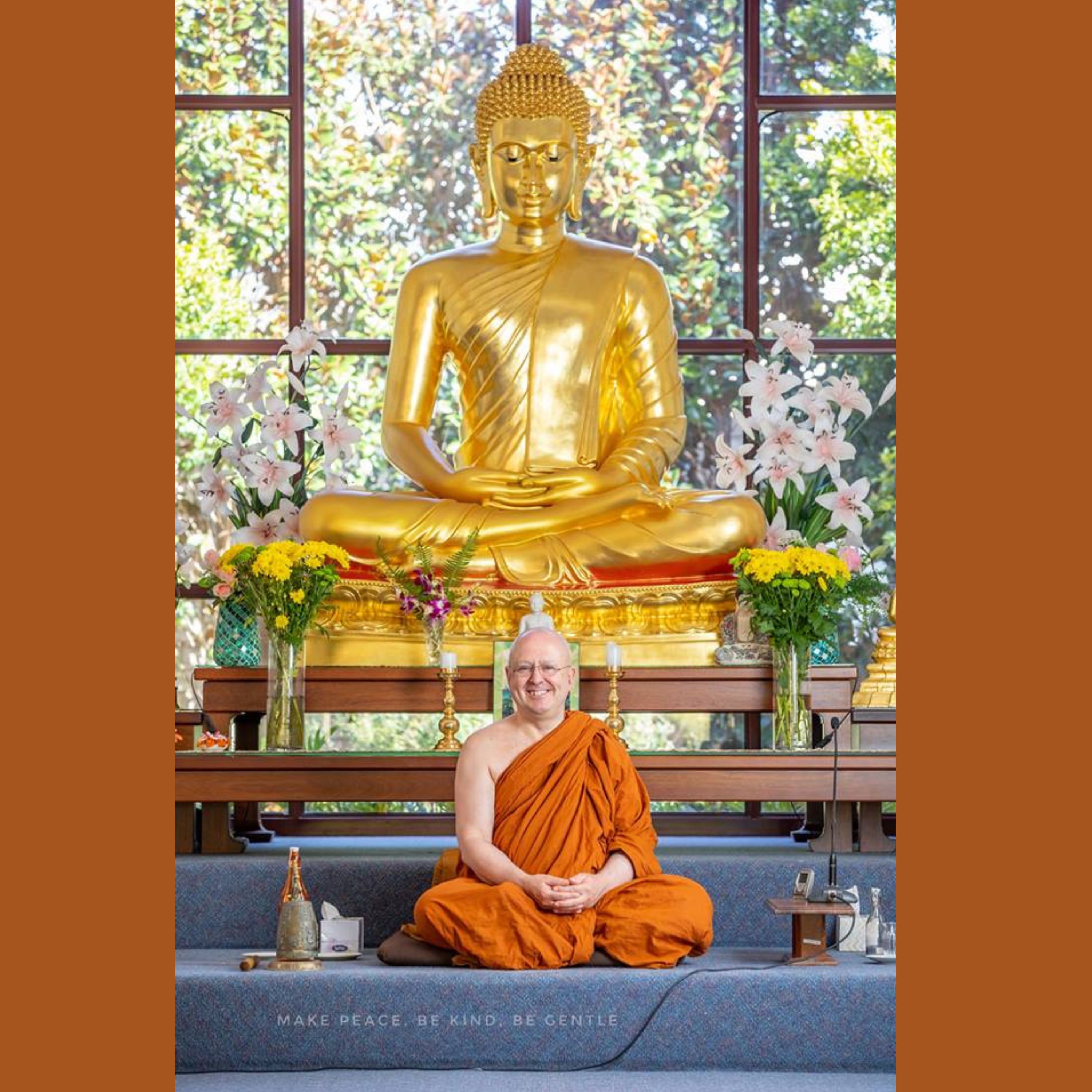

Welcome to these series of talks we're giving for this month of May. And many of you might know that from the advertisements, this is our 30th anniversary of our Buddhist society in West Australia. So giving these series of talks just on some of the basic ideas of Buddhism, and we're starting with a history of Buddhism in order to give people an idea of how Buddhism fits into the history of religions and philosophies and movements of our world. And by giving it that framework, people can actually find their way to understand how Buddhism has developed and how we have the many different traditions of Buddhism, where they all come from, where they all lead to and how it all fits together. This is an overview of the Buddhist world look from a historical perspective, but many of you may have a little idea of Buddhist teachings. And you know that in Buddhism that Buddhists believe in things like reincarnation and the law of karma. That's central to our teachings, but that will be talked about on other lectures coming up later. But I mentioned this because this gives a very wide view of how Buddhists think. And when we talk about our history, you should really mention also about the history of what we call our cosmos of our universe. And as far as Buddhists are concerned, but just as human beings, this life is not their only life. When you talk about history in Buddhism, it goes back not just to the Yusuf universe, but for many universes which preceded this. And so the history in Buddhism is huge, going far back, before the Big Bang, to other universes which existed before that time. And that becomes the uncountable many, many universe idea of Buddhist cosmology. And even in the ancient Buddhist texts, the Buddha himself is quoted as having remembered through his power of meditation 91 eons of existence, 91 universes with their endings and their beginnings. This gives a huge idea of the history in Buddha ##ism but as far as modern history is concerned. In other words, this universe, which here in Buddhism, I always like to mention this because I was a theoretical physicist before myself at Cambridge, and part of the job of theoretical physics is to try and find out the age of this universe. And I was always wondering in the Buddhist text if there's any way of measuring the age of the universe according to Buddhism. And there is. There's one small teaching of the Buddha where it works out that the age of the universe, which is a whole universe from beginning to end. It's roughly about 37,000 million years, which I was very surprised when I read that, because that is pretty much in the ballpark of modern science, where if any of you are in interested in science, you'll find that most scientists put the age of the universe so far from the beginning up till now, at about 13,000 million years. I think it was the last one I read. Sometimes it changes. Giving give 1000 million years here, 1000 million years there, this is 13,000, which is in the ballpark. In other words, and I'm not quite halfway yet. But the history of Buddhism itself started about 2600 years ago with the birth of the person who became our present Buddha. There's many people who look to see about what time that was. And most people these days, through historical records, through monuments, through omes and inscriptions on no stones, put the birth of the Buddha around the year 563 BCE. That's in the 6th century. And that's what most scholars take as the birth of Buddha and the death of the Buddha. The final passing were about 483 BC. Now, to put into perspective that Socrates S was born 470 BC. So the life of the Buddha was like a century before the life of the Greek philosopher Socrates. So it gives you a perspective there of when Buddhism was active and. And to put in perspective the life of the Buddha, which is part of the history Of Buddhism, the Buddha Was born A human being in A small republic in India at that time, in the 7th century BC. That there were some kingdoms and there were some republics. When we talk about republics, it was a republic which was run by a group of the more wealthy and prominent families who would actually sit in a council together and debate and decide upon What Needed To Be decided. We know that because the rules of discipline for the monks and the nuns in Buddhism was based upon the same Legal code as was happening In The republics at that time. So the Buddha himself was born in such a republic. And sometimes people think democracy actually started in Greece, but that's not true, because wherever It started, it was certainly happening in India and 6th century BCE. So the Buddha was born in this republic. However, this republic was a very weak republic of called the Sakians, and there was a kingdom close by which basically told it what to do. It was under the influence and power of a neighboring kingdom. So even though the Buddha was born into one of the wealthy families, he wasn't that powerful. And according to do the myths of Buddhism, you always have to separate the myths of a historical story from what actually happened. As far as we know, the Buddha was a wealthy young man in the sense that as people lived in those days, that he lived in reasonable luxury. And India at that time was turning from an agrarian economy into a surplus economy. In other words, because of good rains, because of roads and the beginning of trade and because of settled villages and towns and all the infrastructure of commerce being available, it did mean that many people for the first time in the history of that part of India were becoming reasonably wealthy and having surplus income so that their work was not always taking up the whole of their time, that they had the opportunity for searching out philosophical ideas, for contemplating religious ideas, and also for just celebrating and having fun. So it was a time of prosperity in that part of India. The part of India which I'm talking about is the Ganges Valley, the River Ganges, which flows from the delta just below what we know now as Calcutta, way up into just past Delhi and up into the mountains. That is all. The Ganges Valley. And that was the area Where the Buddha lived. That was the area Where he taught that was actually the Buddhist land around the Ganges Valley, further to the north and west, the Indus Valley. That was almost like another culture at the time, still having contacts between the two. But the Buddha never really went that far eastwards, confining himself and his religion at the time to the Ganges Valley. And so this was say. A country at that time in which he was born. He was born a very wealthy man and as such had a normal upbringing, married a nice lady but according to the story that he was never content. And the history of the Buddhism of Buddhism really starts with a discontent of the Buddha with material life, especially according to the history of Buddhism. There was an occasion where he saw four important events in his life. Again, this story is part of the myth of Buddhism. But I'm sure it happened in one form or another. But certainly it signified seeing parts of life which were incompatible with his search for pleasure in the ordinary ways. And these form an important part of the Buddhist story of seeing an old man, a sick man, a dead man and a holy man on his tours outside of his home and the seeing of old age, sickness and death and seeing the person who was living very simply without possessions and. Who seemed to be at peace, was the stimulus which led the Buddha to leave his home. It was as if it was a metaphor for seeing the suffering in life, the faults in the search for happiness, to see no matter how much one has, no matter how much one gains, eventually one will have to leave everything behind. And that stimulus related the persons about to become the Buddha to actually to search for happiness outside the normal ways. There was a tradition even before the Buddha, of people who were walking and living in the jungles, who left their home to search for spiritual meaning in their life, to search for enlightenment. And there were teachers who lived in the jungles and the forests of the Ganges valleys who actually taught many philosophies and many ways and many practices. Some were very silly practices, such as going naked or acting as if one was like a cow or a dog. That was described in those ancient suitors, those ancient teachings of the Buddha, that some people even went around on all fours, behaving like a dog, sleeping like a dog, thinking, eating like a dog, thinking that that was going to be a way for enlightenment. People were experimenting with all types of spiritual practices. And according to the story, when the Buddha was 26 years of age, that he left his home to search for spiritual enlightenment amongst this great movement of young people who left the villages and cities to live in the forests and mountains, close to towns and villages to seek for enlightenment. And a means of support was always from arms, food, where a person would go to the village. And the Indian culture at that time and even now, would always support people, whether they were holy or not. People either achieved some stage of realization or some people just on the way to realization. They'd always support these people with the basic necessities of life, which was only just rice and a few vegetables and maybe a few rags for their clothes. It didn't really cost much to support somebody. And so the Buddha went into this great searching mass of human beings who were leaving their material life to search for some deeper meaning. And the Buddha was part of that movement. I need to say that that movement was not just for men. Women also left their home. Women also lived in those jungles and those forests and mountains and also searched for enlightenment. We know that from the stories from that time. And after a long search and trying many different ways, the buddha eventual buddha to be eventually became frustrated because everything he tried so far did not work. And according to the history of the Buddha of Buddhism, the seminal event was in the Buddha s 35th year, where the Buddha sat under a bodhi tree. A bodhi tree is actually a fig tree, which is called bodhi tree because of its significance in the enlightenment, which is the word bodhi in Buddhism. And even today, the Latin name for that tree under which the Buddha sat is called Ficus Religiosis, which means the religious fig tree as it became known to all botanists. And the Buddha sat under this tree. And instead of trying these other ways to become enlightened, the Buddha meditated. The Buddha's meditation came almost naturally. We know as Buddhists that came from experiences in a previous life which he sort of remembered only dimly in his last life and meditating under a tree and a bodhi tree, making his mind very peaceful, very still, very powerful. The Buddha then directed that sort of mind into understanding the nature of the world oneself. And all that is in a nutshell, the way of meditation is the way of stillness. So I can see very clearly. As a simile, which I ve often given here and on my meditation retreats, is a simile of my monastery, which is down in Serpentine. My monastery is up on a hill. And the reason why we build monasteries up on a hill is tradition, because you never see holy men or women living in a swamp. You ever heard of a holy person living in a bog? They'll live on top of hills and mountains, which is why we built our monastery on top of a hill. This tradition even in Australia. So our monastery in Serpentine is on top of a hill, and it's about two and a bit kilometers from the bottom of that hill to the top. And for many years, about ten years since I first went to that monastery, I'd always gone up and down that hill in a vehicle, in a car. And for the first time, after ten years, I decided for exercise to walk up that hill and. When I walked up that hill, the scenery became very different than anything I'd ever seen before. I thought that I knew that hillside because ten years I'd seen it through the window of a car. But when I walked, it looked very different. It was more beautiful, the colors were richer, and I saw far more detail. It was as if it was a completely different and hillside. And then I slowed down and stopped. When I stopped, the hillside looked different again, even more beautiful, more detail, and everything shone much more in greater depth. And I wondered what was going on until I realized that when you're going fast looking through the window of a car, your senses simply don't have time to receive all the information. The eyes and the ears just haven't got the time to see deeply because of that. What you see is dull in its color, it's weak in its detail and you miss so much. But when I slowed down and was walking, my senses, my eyes and my ears, even my nose, had more time to receive much more of what was going on. What I saw was richer in detail and more beautiful. When I stopped, I had all the time in the world to see completely what was going on. When I stopped, that hillside became the most beautiful, the richest in detail. I could see it through. Only I tell that simile as a metaphor for meditation and the arising of wisdom, because most of our life is like going in a fast car through life and. We only catch flashes of what's going on around us. And because of that, we may think we know, but we don't see things truly and fully. When we start to slow down, things become more richer in detail, and even the colors become more beautiful, which is why when one meditates and slows down, everything becomes more beautiful. You see much more all. You see more deeply into the nature of things. And when you stop, that's when it becomes the most beautiful of all. That's when you see fully with all the detail and everything becomes so wonderful. That is a metaphor of meditation. That is what the Buddha did under a podi tree, slowing down, the mind stopping so you can see in full detail now, and richness, not just the hillside, but the nature of oneself, the nature of life, the nature of the universe. The result of that, for the Buddha, is what we call enlightenment. And. Now, this is not a revealed enlightenment from some other being or some prophet. Buddhism really is the only nonprofit religion. That's a joke. It's got no prophets. And so, as such, that that was the beginning of what we know as Buddhism in in our age, a person who looked deeply within themselves, using stillness as a means to see fully and finding out the truth of things again. With that truth came a lot of compassion and kindness as well, which became one of the other hallmarks of Buddhism wisdom, compassion, nonviolence. But those are all teachings which will come later. After becoming enlightened himself, the storybooks say that he spent the next seven weeks just enjoying the bliss of enlightenment. In Buddhism, we always say that enlightenment is happiness, is the ultimate happiness. In other words, to become wise is to become at peace with oneself and become at peace with oneself, and the world is to become really happy. It. And so that happiness turned into bliss for the Buddha ecstasy without any pills, and it lasted for seven whole weeks before the Buddha even thought of going to teach other people. Because it's a nature of human beings that we don't just think of ourselves, we think of others as well. And such was the case with a Buddha thinking of others to see who he could teach. And according to the storybooks that the enlightened itself happened at a small place called Bold Gaia, which again, even now remains one of the pilgrimage places of Buddhism. You go there today, and there's a big temple there where people can go in and actually see the place where the Buddha became enlightened after his enlightenment, he went to another place, just outside of the very famous town of Bernards on the river Ganges, where he had five other friends who were also seeking for enlightenment. And there he taught his first teachings. Their first teachings was what we call the four noble Truths. The four Noble truths. In brief, its usual way of expression is the truth of suffering, its cause, the end of suffering, and away to the end of suffering. But these days, I like to just turn around those teachings to make them more palatable without sacrificing any of the meaning. To say those four noble truths which the Buddha taught as his first teaching in the world was happiness. And the cause of happiness. Why there's no happiness. The. And the reason behind that no happiness. So this is the same as suffering, only turning it around. And that became the basic teachings of the Buddha many times. He always taught, he always said the only things he teaches is happiness and the course of happiness. And so, having taught his first disciples, they, too, became enlightened. And then a whole movement started. Not a movement of messiahs going around specifically trying to convert others, but a movement in which these monks would wander from place to place, and people would see by their actions that they were holy men at peace with the world. And because of their actions, their peace, their smile, that that is why that more people started to ask them, what teachings are you following? What are you doing? And so the movement which we now know as Buddhism blossomed, and many more people joined the community of monks. And as they joined more and more, the movement became very strong. And as the movement became stronger, was not just monks, but then nuns joined. The order had a very strong community of nuns in the time of the Buddha, and also people who were lay people, men and women who also became Buddhists as well, and the lay people who became Buddhists. Many of those attained stages of enlightenment, which were almost as much, sometimes more than the monks and the nuns. The reason why the Buddha established the monasticism for monks and nuns was because it gave the best opportunity for those who had the freedom to do so, to practice meditation, to live simply and devote your whole lives to the realization of truth, and then to the teaching and living of that truth. Some people, even in the time of the Buddha, had wives and husband, children to look after, who had businesses to look after. And so they weren't able to actually to leave the home and join the monastics orders. But nevertheless, they still practiced their meditation, kept their precepts, and achieved much wisdom and much peace in their lives. Because there was a non of violent religion, because it was a tolerant religion. Once one of the chief members of a particular city, a very powerful city, a city called Nalanda, for those of you who are interested in this story, one of the chief members of this city, who was the General of the Imperial Army, went to see the Buddha, to try and convert the Buddha to becoming a Jain. In the time of the Buddha, that was the other popular religion, Jainism, that was also in India, in the Ganges Valleys at the same time, those religions were contemporary. And he went to try and convert the Buddha, and it ended up the Buddha converted him. He was so impressed by the Buddha s teachings, especially when he said, I-M-A Buddhist now. Should I still give arms to the Jains? And he said, of course you should. You ve long been known as a supporter for this other religion. Please keep on supporting and giving arms, food and clothing to those monks and those nuns. And when the person heard this, they realized just how tolerant the Buddhists were. They weren't even trying to look down upon other religions and still telling the Buddhists to support other people as well, to be kind and be compassionate. That tolerance has always been there with Buddhism. There has never been a war fought in the name of Buddhism. Whatever country Buddhists have gone to, they've always lived at peace with people of other face, other religions. In Buddhism, we've never gone around knocking on doors, not even ringing doorbells. And I'm very proud of that. So the first monks were started. Actually, it's well established that the aven idea of monasticism started with Buddhism. It was the only religion which had that from its very start, which had it as a direct consequence of its teachings of leaving the world. And it's understood by many people these days that it was from Buddhist monasticism, especially when it went to Egypt, that we have Christian monasticism as on the side of the history of Buddhism. This is one of my little core celebs that about 200 years after the passing away of the Buddha, there was an emperor called Asoka who became a strong supporter of Buddhism and also nonviolence. He started off as a very violent emperor, and after one particular bloody war, where he killed so many people and many people were put into slavery, and where he wrote on stone pillars, which still exists today, which are very easy to decipher about the pain and misery that a war causes. Not just for the people killed, but for the relations. The wives who no longer have husbands, the mothers who mourn their sons and. That he became so upset at his conduct and the pain of war that he saw a Buddhist monk talk to him and realizing the nonviolence of Buddhism, became a Buddhist himself and stopped killing? Who ordered that even the animals in India should not be killed? Who made sure all his palaces were vegetarian and even put hospitals for animals in India? About 200, 300 years before Jesus Christ was born, he was named the Emperor Soka. But at that time, from the records, we know this is his history, because he left these stone pillars throughout the whole of India which were lost into the jungle. But in the time of the British Empire in India, the archaeologists from the British Empire uncovered these stone pillars are still being uncovered to this day, in which the inscriptions are still readable, in which you see his orders to the kingdom over 2200 years ago. And. Not only to be vegetarians, but to try and keep righteousness, to look after the people, but in particular a few pillars. He sent emissaries, ambassadors with religious ambassadors alongside to many places, including the Ptolemies of Egypt. We know from history that he sent monks to the Ptolemies in Egypt. It we know also from history that at the turn of the millennium, over 2000 years ago, there was a strong monastery in Alexandria which was run by a group of monks called the Terra Putai. Those Terra Putai were described by a Greek historian called Philo of Alexandria. They were described as having bald heads, not tonschers like the Christian monks, but fully bald heads, wearing brown robes, being vegetarian and many other things which were only specific to Buddhist monks. And indeed, the word Terra Putai derives from the word Terravada, which is one of the great sects of Buddhism to which the this monk belongs. It's almost certain that 2000 years ago there was a thriving monastery in Alexandria in Upper Egypt, the capital of Egypt at the time, from which eventually monasticism in Christianity started. And. The original Christian monastics were the desert fathers of Egypt, of Lower Egypt. And from that we get our monasteries, Christian monasteries today. But that's another story. I'm going back now to the time of the Buddha. After establishing many monks, many nuns, many lay people, many lay women, the Buddha passed away somewhere around the year. What most is Dorians think is around 486 BCE, around 500 years before the birth of Christ. By that time, his movement was very strong. One of the interesting things about the Buddhist movement, when the monks asked him, will you appoint a successor? He said no. He said, Let my teachings what I've laid down, and the rules for you monks, let they be your teacher. And so not appointing a successor meant there was a certain degree of freedom forever in Buddhism. The monks and nuns will look at those teachings, would interpret them each in their own way, but there'll never be any overarching authority to say what is right and what is wrong. So even today, there is no pope, there is no Archbishop of Canterbury, there is no overall leader in Buddhism. And every Buddhist community is independent of the others, which prospers or declines according to its own efforts, its own goodness, its own purity. And it's a different way of growth, almost like an organic growth for each community. If it's a good group of monks, nuns, teachers, leaders, then it will grow. If it's not, it will decline. And. And so when the Buddha died, he left the teachings as his successor. And so shortly after that, the monks had to meet together Dutch to decide exactly what were those teachings which to be their guide forevermore. And so there's what we call the first council. When all of the teachings were grouped together, they weren't written down, because in India at that time, it was considered to almost sacrilegious, actually, to write down teachings. Writing was considered to be confined to business operations, nothing more than that. Or maybe the business of government, trade, that sort of stuff. They would never actually write down the Buddhist teachings, but instead they'd be memorized. Sometimes people say, how can you memorize such teachings without forgetting them? But I've known some actors who've become monks. One particular actor was a contemporary of that time, just a mate of his. Joined the national theater together with a guy called Tony Hopkins, who's now Sir Anthony Hopkins. He became Hannibal Lecter, and my friend became a tervata monk. One eats vegetarian, the other one eats human brains. It. But he can still remember much of shakespeare. There are many people who could have a phenomenal memory if you re a trained actor. And at this time, that these monks would retain whole teachings of the buddha, but they would always be tested from time to time. It was part of monastic life at the time to meet together, to recite these things, to make sure you made no mistake. S and that's the way those teachings were looked after for many years until about the first century before christ. Some monks in Sri Lanka wrote those down for the first time, and these became like the scriptures of buddhism. But between that time of writing down, the buddhism grew in India, and many monasteries were established. And like many institutions, some of those monasteries, because they were in the cities, because they were well supported, they did become decadent. Originally, the buddhism started in the jungles and forests, where the monks would spend most of the time sleeping out under the trees, meditating, having very few possessions, like any other religion. When it becomes famous, it becomes rich. When it becomes rich, it becomes lax. When it becomes lax, it can become decadent. But because there was no overarching authority, it. The people would eventually not support the lax monks and nuns and put their support to the good ones. It was an unnatural growth and decline of buddhism. Just like trees grow in the forest, if the seed is good, then you get a very wonderful tree. Eventually that wonderful tree when it gets old and decays and starts falling down and is dead. But during that time, it creates many seeds which make young trees, vibrant trees elsewhere. And so buddhism has always spread beautiful seeds from a good tree. As the tree grows old and decadent, the young seed grows into fullness and rightness so this became buddhism. As it spread through India, it spread over to the west. It spread as far as what is now Afghanistan. And you all remember that a few years ago, the great buddhist statues at bamiyan were destroyed by the Taliban soldiers. At the time I was happened to be in India on a pilgrimage. Now, again, I was very impressed that even though those statues were destroyed, the Buddhists never respond. Did with violence back. Because as far as Buddhists are concerned, statues are just representatives of something much deeper. They're representing qualities such as virtue, nonviolence compassion, peace. So it's more important the Buddhists kept what those statues represented peace and tolerance and forgiveness, rather than allow the Taliban to destroy not only the statues, but to destroy what they stood for by responding with violence. But Buddhism was that pacifist religion. It always has been, and spread into the west very strongly, through Afghanistan, into parts of Iran, and, according to many, into Alexandria in Egypt, and also to parts of Europe as well. It's interesting on that particular angle that one of the first printed books was the Gutenberg Bible. In those first printed books, the Gutenberg Bible that the printer also put little what you call today cartoons, little pictures from page to page and under the Psalms, one of those pictures is very clear a Buddhist monk. What a picture of Buddhist monk is doing in a 15th century Christian bible printed in Germany, no one now knows, but whatever the author, the printer, certainly knew of the existence of Buddhist monks in Europe at that time. And even more interesting in the 13th century cathedral of Bambourg in Germany is also in the stone work of the cathedral. Very clearly a picture of a Buddhist monk, a carving. We don't know why they're there, but certainly 13th century, 14th, 15th century Europe was very aware of buddhist monks and Buddhism. Now back to India and the spread of Buddhism. But as Buddhism grew, the goal was always the goal of enlightenment. And like many goals, that sometimes people thought it was too hard to become enlightened, according to the Buddha, that you had to give up so much and so, quite naturally, that some groups gave an easier way to enlightenment. People always like the easier way. I sometimes think it's similar to our university s there are many universities which have a very high standard, but if they're not careful, that high standard gets lowered and lowered and lowered simply by demand to the point. There are some universities I've here in United States, we don't need to even do an assignment. Just send $100 and you get a degree. That's the extreme. And sometimes you can see the same trend happening in early Buddhism. Instead of having to work so hard to become enlightened, maybe you didn't have to work so hard as well. And so some traditions offered an easier way to enlightenment. And so you see in the spiritual marketplace of India at that time that some people had easier ways, not asking so much of the people who became enlightened. And actually, you see in the history of Buddhism that a certain document was written by a monk called Mahadewa about 200 years, 300 years after the passing away of the Buddha, just saying, enlightened being doesn't need to be so pure, so wise. Enlightened being can make mistakes. What it was doing there was lowering the requirement for enlightenment. And at the same time that there was political pressure amongst the community of monks, which basically were the authorities in Buddhism at the time. And. About who would make decisions, whether it was the monks were fully enlightened, almost like an aristocracy, an elite group of monks, or whether all the monks should have one monk, one vote, as was the original republics out of which Buddhism grew. And because of one particular time that there was almost split and they asked a group of enlightened monks to decide and they decided against the majority. From that time on, there was always seen in Buddhism a splitting of the traditions, both political and also on the goal of enlightenment and eventually led many different sets of Buddhism. Those sects were very similar to begin the beginning and they're also very tolerant. Books show us that monks could go to ediculous sect and they were welcomed as just some of their teachings would be slightly different. There was a tolerance, the difference of opinions and. But because of the separation of distances and monasteries becoming famous in one area and famous in other areas, those splits grew and grew and grew. And with the splits came different nuances in the philosophy of buddhism. And out of those splits came the idea of an alternative to enlightenment, which was someone who puts off their enlightenment in order to help other beings. And this became the other strand of buddhism, the great strand, which we call mahayana, the great vehicle. So these were people, even monks, who said, maybe I won't strive so hard for my own enlightenment because that would mean like leaving, never coming back again. Maybe I should work hard for others first of all. And there's always been much debate whether that idea made sense or not, but it did create a whole different type of buddhism called the mahayana. And those teachings came about around the first century BC. And they grew in the next two or 300 years, they lived alongside the other teachings of buddhism. And there were great debates and arguments for most of the monks. And the nuns at that time just did their little meditations in the forest and never had too much time to actually to argue. They were more interested in living peacefully together. But it was in the great centers, the great monasteries within the towns and villages within the towns and cities sorry where books started to be written, treatises, treatises on Buddhism. Buddhism grew and developed, and other ideas were allowed to exist within it. Until we come to roughly the 12th century or 13th century in our era, when the Muslim invasion eventually reached India and overwhelmed the ganges valley and thereby destroyed all of Buddhism in that land. Many of the monks fled north woods. Some of them fled eastwards. The ones who fled northwards went into the land which is now called Tibet, and they took their teachings with them. And those teachings became eventually what we know now as Tibetan Buddhism. Beforehand, some of the monks had fled south into the southern India and to Sri Lanka, and they took the teachings, which we now call tel Avivada Buddhism. Even earlier, around the second century Ad. Some monks actually, some people traveled from China and brought back books and. And brought back teachings and established the many different sects of Buddhism in China. But after the Muslim invasion, the core headquarters of Buddhism was destroyed. And really from that time on, those different traditions, having no contact with each other, basically having no more head office, diverged greatly from each other simply because of distance. Other were added, some lost. And so we had three great traditions of Buddhism, simply because of the migrations of monks and the isolation for many years after the 12th 13th century invasions of India again. In Tibet and Mongolia, surrounding areas of Nepal, we have the Tibetan Buddhism, Wajriana, and in China, we had the great Mahayana traditions, including traditions like Zen, which eventually went to Korea and Japan. And in Sri Lanka that tradition spread to Thailand and Burma and Sri Lanka, Laos and Cambodia. So we had these three great traditions which grew from time to time and. For many years, those traditions had no contact with each other. But in our modern age, those traditions have eventually come together. And so marks of those different traditions, they do meet together, and they do compare notes, they do compare the scriptures of their traditions and to see maybe which is closer to the original teachings of the Buddha. For whatever those different traditions which we have, we all know they came from that common source. And some of the different ways of doing things is just because of the cultural needs of that place. For example, the traditions which went to Sri Lanka and Burma, Laos, Cambodia, Thailand, those traditions could keep the original, say, rules of discipline of a Buddhist monk, the same type of robes, the same type of eating habits. For those monks who went to Tibet and maybe northern China because of the cold, many of them required to eat an extra meal in the evening, they had different robes simply because it needed to keep warm. Different things happened in those different places. Different teachings became popular, and the whole thing evolved. But it evolved still, keeping the kernel of the original Buddhist teachings. And so now, in our modern age, when a Terravada monk being the tradition which was in Thailand, Burma, Laos, Sri Lanka, Cambodia, when they meet a Tibetan monk or a Mahayana monk from. Like China Hong Kong, Taiwan, or Japan, Korea, there is still so much in common which we have. We go to our core Buddhist teachings. But even though, because of the spread of Buddhism to those different lands, there have been differences of dress and differences of emphasis, this is a person observation of one who actually does go and visit these monks from different lands, different places. There's much more that we have in common so that we can be great friends, that we can have a common core of teachings which none of us argue about. So that was actually the spread of Buddhism, and that was its history from the very beginnings to the ends of our present day. It and this is actually how Buddhism developed. It developed organically, each community depending upon its own goodness, the way it could inspire people or not inspire people. If it didn't have good teachings, it wouldn't inspire people, and it would die. If it had good teachings and good examples of good monks, good nuns, good laymen, and good lay women, then it would grow. As it always will do, as it has done. So that, in a nutshell, is the history of Buddhism up to now. Now, I'm going to invite any questions, because there is an old teaching in Buddhism which I'd like to share with you. Now, I already mentioned the importance of calm and rebirth of Buddhists. And in one particular teaching, one particular scripture which records the teachings of the Buddha. The Buddha described like the reasons why some people are born into a rich family, while others are reborn into a poor family, while some people are reborn beautiful, while others are reborn ugly. And in particular, he taught the Karmic reasons why some people are born intelligent in their next lives, while other people will be reborn stupid. And the reason the Buddha said why people are born stupid in their next lives is because they don't ask questions in this one. So for that reason, I now ask any questions. Does anyone want to be reborn? Any questions about the history of Buddhism so far? Yes? Become practice person. That's a very good question. How does a person become a Buddhist? I can tell my own story, which is typical about how a person becomes a Buddhist in our day and age. So when I was 16, I got my first school prize for mathematics, and this first school prize I ever won. I came good towards the end of my school life, which is probably the most fortunate time to do well. And not knowing what to do with the school prize, I asked my math teacher to the prize in mathematics, what should I do with this? And he told me to go to a big bookshop in London called Foils in Tottenham Court Road and to go and get some books on maths, because then you do even better next year. So when I went up to this bookshop and looked at these books on mathematics, looked so boring and dull, I thought, no way am I going to spend my first school prize on this rubbish. On the opposite side of the road, in the annex, on the top story was all these books on sort of occult things like ghosts and Eastern religions and philosophy, psychology, all these things which were banned in school at the time. So I thought, that's what I'd get. And. So in particular, I saw all these books on the different religions of the world, and I got a copy of the Quran, I got a copy of the Bhagwad Gita from Hinduism, got a copy of a book on Buddhism. Because also at the time, I thought that the only rational way to choose a religion in life was actually to read about each one. It's like going through choice magazine to find what car you want. And so I looked at these books and read them out for myself. Read them for myself. And the book which really made a lot of sense to me was a book on Buddhism. From that time on, I started calling myself a Buddhist. Even though I had gone through no initiation, even though I didn't even know any other Buddhists in in the whole world. I went around calling myself a Buddhist simply because that made sense to me. And for many people, that's how the become a Buddhist. Simply they come across these teachings. It makes sense to them. They think that's them. It wasn't that their first book which I read was teaching me anything new. It was that all that I saw, all that I knew. The way I looked at the world had a name, and it was Buddhism. It was shared with many other people. It. So that's actually how one really becomes a Buddhist, or one should really become a Christian or a Muslim or whatever has to come in the heart, first of all. But then later on that one can express sort of that interest in the religion by going through a ceremony of usually taking three refugees in the Buddha. Dhammad Sangha that's a little ceremony which we can go through if one really wants to say, yeah, I really am Buddhist. This is similar to actually when you find your partner in life, you fall in love. You have that inner commitment to that person, and actually, that's it, really. You fell in love. That's the person you want to live with for the rest of your life as long as possible, and he wants to live with you. But a marriage is important because that makes that commitment more open so others can see it in the same way that really becoming a Buddhist is an internal thing, which you really don't need a ceremony for, you know, well, this is me. But then afterwards you go through a ceremony just to make it more open and. Maybe for others or maybe for yourself, it really depends. So there is a ceremony. But real becoming a Buddhist is actually an eternal thing, as it should be. Becoming a Christian, becoming a Muslim, you can't wave a magic wand or go to a ceremony. Now you're a Buddhist, before you weren't. Now you're a Christian, before you weren't. It's more deep than that. But thank you. That's a very good question. 9s Yes, why not? There are many people, as many Jewish people in the United States are becoming Buddhists, but they're Jewish by race, Buddhists by inclination. So, like, you know, being in the US, they've got a name for these people. They call them Jew buds. That's so why not? Especially when I'm always interested. And you may not hear other people say this thing about the Buddhist symptoms of Christianity, but no, buddhism was five or six centuries before Christianity started. And I think you may know that Christianity had three great strands in the very beginning. There was Jewish Christianity, gentile Christianity, Paul, and there was also Gnostic Christianity. Those three great strands of Christianity which were there at the beginning, were actually vying for supremacy, and the Jewish Christianity, which was not really making a new religion, but adapting Judaism according to Jesus s teachings. Because I think even Jesus said in the Bible that I did not come to overturn the law, but to fulfill the law of Judaism. So many people quoted that that sort of Christianity should be within Judaism. But then there was the Romans, the Roman Christians, who wanted to make it separate. That's why there's so much controversy over whether you should have Christians should be circumcised or not and what they should do, what they shouldn't do with the Jewish food rules. There's also the Gnostic Christianity as well, which was much more an individual spirit, what we call almost like a spiritual religion of relying upon oneself for truth. And of those three great traditions, the Jewish Christianity was destroyed in 70 Ad with the destruction by the Roman Empire of the Jewish Temple in Jerusalem. That was when they destroyed that temple, one football. And that left just the Roman Christians and the Gnostics. The gnostics were completely disorganized. They didn't have, like, leaders and bishops and such the top down organization like the Roman Christians learned to have. But little by little they were persecuted until they were completely annihilated. And the Christianity centered on Rome, dominated the Christianity which we know today. But interestingly enough, you can never really suppress anything in this world, even though the early Christians destroyed so many documents and churches of the Gnostics. Just, I think in 1948, in the south of Egypt, an archaeologist came across some ancient papyrus which actually a shepherd was burning as using as kindling for his fire. And these were Agnostic gospels, which were, I think, second or third century and. And these were sayings of Jesus Christ, purportedly. And they've been translated. They were interesting found about the same time as the Dead Sea Scrolls. Whereas the Dead Sea Scrolls were describing a group of monks called Theocenes, these scrolls were describing something much a little bit later, but actually after the time of Jesus Christ. And they were purporting to have saying of Jesus a completely different strand of Christianity. They're very interesting to read. If you want to find out another strand of early Christianity, one of the best books to read, or you can look on the Internet and Amazon, whatever, or bookshop. Elaine Pegels was one of the translators and she did an overview as well as a full translation of some of these gnostic gospels. That's P-A-G-E-L-S. Elaine pagels. They're interesting to read. Some of the things which were actually second century, third century, I forget which. Saying. We're actually sayings of Jesus, which you don't find in the other Bible. If you look at those and look at Buddhism, then there is huge amounts of similarities. It's interesting. So that's why yeah. Why not? Christian? Buddhist or Buddhist christian. That's why my name Ajan Brahm. You know what brahm means? Love? If you know this one, it's B for Buddhist. This is my name. R for Roman Catholic, a for Anglican, h for Hindu, and M for Muslim. Bra. 11s Have another question. Yes. The three six wajriana and the Terravada. Yeah. The diversity, practice and style. Again, it's a generalization because within each group there's a huge range of different ideas and practices. Because, for example, this is I'm a terravada mon, but our tradition, called the forest tradition, is quite an austere tradition. We don't keep or handle any money and we don't watch TVs, radios, eat only in the morning time, not in the afternoon. So this is like an austere tradition which we try and keep as close to what we know of original Buddhism as possible. We can do this because we live in usually warm countries. The practices of Tibetan Buddhism and Mahayana Buddhism again, such a huge range of this is but because of political influence. For example, in Japan, the Zeden monks were always celibate until one of the emperors decreed that all the monks had to get married. It was actually decreed from above. And basically, in those times, Japanese shoguns had such immense power, it was either do that or die. So from that time on, in Japan, the monks would not celebrate anymore. So the monks would monks. But they'd also have wives as well. And in Buddhist Buddhism, we have some of the Tibetan monks are celibate, like in the Dalai Lamas group. Other monks aunts have wives. So, again, it's sometimes different sects do different things from different ideas. But when we get to the heart of the teachings because all of those traditions accept that we all having the same core teachings of the Buddha. Because all those teachings which actually went to Sri Lanka and went to Tibet, to Thailand and Cambodia, laos, Burma, also went to Tibet and also went to China, also went to Japan they're all considered to be authentic Buddhist teachings. But we all added other ones on top of those. And. And so the Tibetans added a huge number of other ones, and the Chinese, because they didn t have too much idea which teaching came first, which came afterwards, also had a huge number of other teachings as well. And so I'd like to give a simile that each of those traditions and all of the variances within those traditions can be looked up on rows, like different cakes in a cake shop. And they've all got different icings on the top. Some have got really thick icings on the top, and they look very, very different. But if you go into the heart of the cake, you always find the same cake mix and the same taste in the middle of all those traditions. But some have got lots of thick icing on the top. You have to dig very deeply, actually, to find the what's really underneath it. So I've only got thin icings. If you go inside, you actually find all those teachings. The practices are the same. That's why you can be friends with all those monks. When you get down to maybe what not what you're teaching, what actually you doing and. You know, what's actually in the heart of peace, what actually do you experience when you meditate with your zedd monk or Tibetan monk or a terabarda monk? You experience the same. What is compassion for a Tibetan monk or a Vietnamese monk or a Thai monk? It's the same. So when you go into the heart of those things, it's very, very similar. But when we actually add all the different ceremonies, the different robes, the different ways of teaching things, then it may look very different. The charting may be different, but why we do it is the same. Does that sort of make sense? That was what you're really asking. Okay, now please come back, because you're always allowed to ask questions and because the Buddha said that after I'm dead, you can't have any sort of authority as the absolute authority. It's always allowable to argue with a monk or with a nun and say, listen, I don't agree with that's. A lot of rubbish, but. So just because I sit up here doesn't mean I'm always right. So please argue. Any questions over here? Yes. How did karma come about that karma was there from the very beginning, even actually be before Buddhism, that people in India accepted rebirth. Their witness wasn't the first life. And also the law of karma as well. And we can't really say that was like an Indian invention, because that was there in ancient Greece as well. Socrates, Plato, Pythagoras, Heraclitus they were all teaching, no rebirth. And karma? Anyone who wishes to find out, go and read Plato's Republic. The last chapter was the so called Socrates idea of the law of karma and rebirth. Certainly fascinating that his description was supposedly by a person who remembered what happened from one life to the next and wrote it down. And Plato recorded it in his Republic. And in that one that when a person dies, they go off to the you may remember this in some movies, Elysian Fields, where you you rest for a while, and then when it's time for you to get your rebirth this is Plato's idea of rebirth. Actually not really such a law of karma, but actually you can choose whichever rebirth you want. Whether you want to reborn as a general or just a farmer or just a rich person or a poor person, you actually choose. It's interesting that that's very similar to Buddhist idea of karma. You're actually inclined you want to do these things. And then he said, some stupid people want to become generals or very rich. And Plato was saying, the wise people just want to be ordinary people, because those who are very, very rich and famous don't have much freedom. Those are very, very poor, have lots of suffering. But the average Joe or average Joanne, whatever it is, they have a life of greatest happiness or greatest potential happiness. They don't have to face public, don't have to go to war. They don't have to worry about kings and robbers robbing them. So it's the average person, Plato said, was always the best. And then he said, once you've got your little new life, then you go across this river lease to go to your new life, where you forget all that's happened before you come into this new life oblivious of your previous existence. That's in Plato's Republic. So you can actually have a read of that if you like. Sort of ancient Greek idea of rebirth. But it's quite likely that was actually influenced by Buddhism, because we certainly know that by that time, the Marx were traveling around 100 years. Socrates, this was when Socrates was born. Hundred years after the Buddha was born. Plato many years after. Sometimes we don't realize the contact there was between India and Europe. The same time as this, the first century BC. There was an ancient map of Alexandria, there s quite a few which people would draw and they re still around in libraries which showed written down a very strong Indian quarter, just like we have Chinatown in many towns. Because that's a place where chinese traders would have their offices, where they would import bought goods from china to sell and they'd export goods back to china. In that time, there was Indian traders expats and there was enough of them in Alexandria, which was the capital city of Egypt at the time. There was plenty of them there. They had their own little quarter, first century BC. They were importing goods. India the trade route has been well established. Over to the west coast of India, to the port of Saparaka, and then up the Arabian Gulf by sea, port to port to port, because overland was too dangerous, and up the Red Sea. And then overland from the Red Sea to Alexandria. And then from Alexandria fanning out to the European the European civilization and the European goods going to Alexandria and then going backwards with the traders there. That was an old trade route which has been well established. So there were many Indians in Upper Egypt, first century BC. And of course, they brought their monks with them. That's where the first monastery started from. I will say it's very interesting, very fascinating. Those of you who were brought up as Christians, this is the answering the question is okay to be a Christian and a Buddhist? According to the Christian Bible. When I think Herod did his purge of young Babe peace in Palestine, where did Jesus family flee to? Where did they go? Egypt. Yeah. What town did they go to, do you reckon? There was no Cairo at that time. It just probably be of a village. They went to Alexandria. That's not said in the Bible, but it's absolutely certain that's where they went, as all refugees will go to the capital city to seek work, to seek shelter. So it's quite clear to me anyway, that if that's true, that Jesus actually fled to Alexandria, where he spent his first years before formative years, you certainly would have come across a Terra Putai, who one of the most famous group of spiritual people in the city at the time, according to Felip. Alexandria we certainly learned a lot from the Buddhist monks, so it's not that much difference with original Christianity and Buddhism. There's a history of Buddhism so that gives like an overview of actually what happened. And in fact, there are many different sects. We get on really, really well. It's much even closer than the Catholics and the Anglicans. So I thank you all for coming to join into this little session today. There'll be another session next week where we go more into some of the teachings of Buddhism. And I think the teaching next week is going to be we're supposed to be on meditation, meditation and nature of mind in Buddhism. So here we actually do a little overview of the theory of meditation, why meditation and also the nature of mind in Buddhism. That's coming up next week.