Episode Transcript

Which Yana? Hahayana!

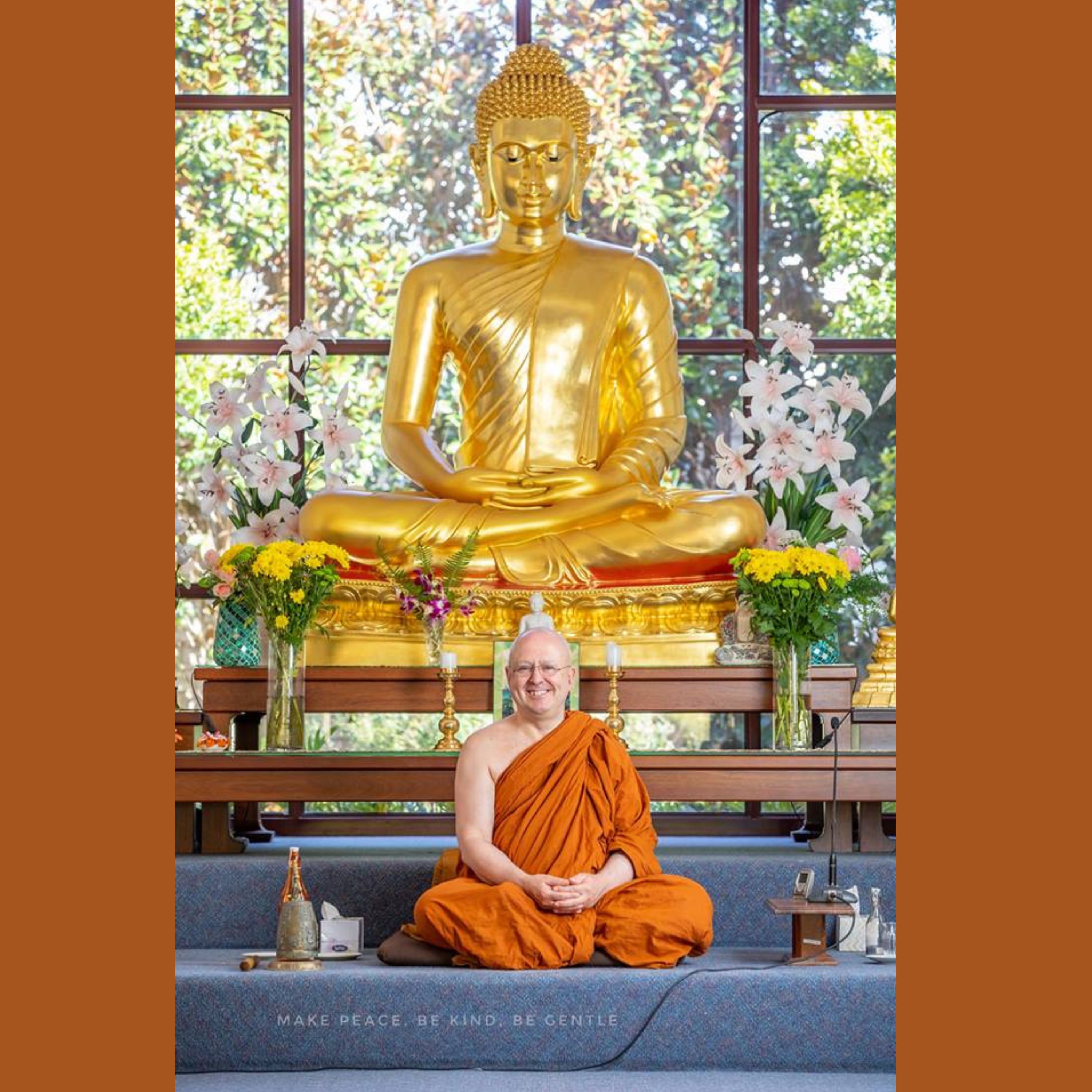

By Ajahn Brahm

Okay, well, the last two people are finding their space in the floor. This is the subject for this evening is another request. This time that somebody has sent a letter from the Netherlands. It was an English young Englishman starting over there who's been listening to all these talks on the internet. It's amazing just how many of these talks on a Friday night go all around the world. First of all, just on audio and now on the webcam. So we've got a huge audience. And this particular person, a young man who's now got very interested in Buddhism, asked me a question which I thought was worthy of addressing on a Friday night. It's an old question, but a powerful one, and I'm going to answer it in a different way than I've answered before, because all these talks are, you know, ad hoc. The particular question was that he's come across our our tradition, Theravada forest tradition originated in Thailand, and he's come across other traditions as well, though, especially the Mahayana. And he's read many books and said, what's the difference between all these traditions? Is there a difference and how do they overlay together? Or don't they relate at all? What is the meaning to the different traditions in Buddhism? And that's the subject of this evening's talk. I will obviously have to address this in a historical, academic way, first of all, but please don't get disappointed because later on in the talk, as soon as I possibly can, I'm going to take this academic, uh, treatment and find its heart to wring out of it. So the real truth about what's going on. And also just to see just how the right attitudes, which we have to even the historic treatment of the different strands of Buddhism, can also be applied to many other aspects of our life and also our relationship to other religions, other points of view, other ways of thinking. So we can get what religions are supposed to be providing a way forward harmony, peace and friendship in our world. But we have to go back to the time of the Buddha, because when a Buddha became enlightened, he never taught Buddhism Theravada, Mahayana, adrianna's or anything. He taught what we call the Dharma. And that means the truth. And even these days, people argue about dumsor about how to spell it. Should it be d h a? I am a r d a double m. What a stupid thing to waste your time on. I don't care how the how you pronounce or how you spell it, but the point is, what it means is important. And this word Dhamma, what the Buddha actually found and what he taught has incredibly rich meaning. It can mean the truth, it can mean the law, but it means that what's at the heart of things, the source, what keeps things running, what's underlying everything, and what's at the heart of you as well? Whenever we look at any experience, it's where it's coming from and what causes it. What is its source? What is it that is the meaning of dumb. And that's what the Buddha thought. However when anybody tries to explain, you know, what is as a single experience, you usually guided meditation. People start taking the explanations and the descriptions to be the real thing, the truth. And as you've heard me say here many times, the menu is not the food, the map is not the territory. The explanation is not the meaning. So a lot of times the problems come when we just take the words which the Buddha was using to describe certain events and just worship those words rather than worship what they were pointing to. But however, you do need explanations, you do need teachings. You do need words to try and explain these things. And so we start getting Eightfold Path or Noble Truths or these little things which you read in books, which is you say it's Buddhism, it's not Buddhism. It's not Dharma is what is pointing to the Buddhism, what is pointing to Dharma. The truth is, uh, point to the encapsulated there. It's wrapped up in there. But you have to take the wrappings off and say, what does this really mean? Was it pointing to. To really understand what Dharma is, which is why that all those words and all those books, all those explanations, they are there to be contemplated upon using the power which is conferred upon every individual by deep meditation. Use a deep meditation. You've got all those teachings. You put the two together is called putting the match onto the gunpowder. There is a bang. Enlightenment happens. For those of you who wants to actually to check me out upon this. This isn't the cause for seeing the Dharma for becoming a story winner. So one. They have the two courses, they have to come together. And those two courses for seeing and penetrating the truth, seeing the Dhamma for yourself, becoming a one who enters a stream in Sri Lanka, they called it. So one is the words from another, someone else who seen that dharma, the truth that is that the map, that is the menu, that is the books, the word of another. But the other important thing, virtue penetrating that truth is called impartially. Yoni sir. Mana seeker literally means word to work of the mind which goes to the source, the essence of things. Now, when you've been meditating, where are you going? You're going here, into this moment, into the silence, into the present, right into this mind, into the centre of things. That's what the work of the mind is. So traditionally in all types of Buddhism. That you have the teachings, you have the practice. When the two come together. That is where enlightenment happens. So we had this great teachings and that was the essence of them. But what happens, like a lot of the times, people prefer to talk about Buddhism rather than practice it. They prefer to write about it and become famous rather than just sit in quiet monasteries and just disappear. And so because of that, there's lots of explanations on how to do it. Sometimes you'll wonder, is there too many explanations? Are there too many books in the library? Are there too many talks? I've just seen in our library, there's a whole MP3 series of about 100 talks of John Brown. My goodness. Only what is enough? You've heard one. You've heard them all. That's what I say. That's why you keep coming personally. But nevertheless, people love information. And because they love information, they like to listen to this teachings put in a different way, a more entertaining way. You see from this angle, you see it from that angle. But the essence is always the same. And so because people were seeing it from different angles, we got different ways of teaching different teachings of the Buddha and the other great teachers of that time. Or if you can really understand and penetrated for yourself, or going to the same essence but just from different angles. However, just what happened once the Buddha passed away and we celebrated that last week he did an amazing, um, suggestion, a statement which became a rule. He said after I pass away. There will be no leader. There will be no pope. No archbishop. No head honcho. For actually to be the apex of Buddhism from here on, he said. Instead, let the Dhamma let the truth be your leader, be your teacher. Now, that was a unique and powerful statement made by obviously one of the wisest, most enlightened beings we've ever walked on this planet. Because at one stroke, he sort of stopped all these power games of an organized religion. So no one, no monk, no lama, no priest can actually put themselves up and say they're the head Buddhist because the Buddha specifically said, no way. The teacher, the leader. The peak can never be a pope, can never be an archbishop, can never be sort of the the Supreme Patriarch. Or it can be is the dharma, the teaching. So straight away it takes away, you know, from any hierarchy, any really powerful hierarchy, and gives dharma to where it belongs to each individual. Nevertheless, because because of human nature, there would always be people in authority. And a lot of times those people in authority, they are given that authority by their supporters. Be careful because you make those patriarchs, not the people themselves, but you put them in those positions. And that's a dangerous thing to do. But anyhow, the main patriarch, if you like, of Buddhism, wasn't actually a person. It became the sangha is a group of monastics, and especially there was the elites amongst the monastics. And what was that elite was the enlightened ones. There was a natural elitism there, and it's very hard to stop it. Those monks who were enlightened and those nuns who were enlightened, they obviously became sort of natural authorities If you really want to ask a question on Buddhism, on dharma, on meditation, who would you ask? Obviously you want to go and ask an enlightened one. The one who has got all of the answers. Now, even though in Buddhism the Buddha actually laid down all these rules to say, don't let anyone know if you're enlightened, don't exhibit your psychic powers so that, you know, you sort of suppress any elitism, even to the point that all the monks and the nuns, they wear the same type of robes. I just got a new robe. It wasn't big enough, so put a patch on. The end of it is a different color. I am proud of having a patch robe, because sometimes people think that if you become like an abbot, you have to have the lamé robe. Another one because sparkles. Well, at least you can have a few sort of stripes to show your authority. But if you didn't came to our monastery for the first time, you wouldn't know who is a senior monk and who was a junior monk. Because we look the same. It's the same as Dharma. So as well. If you've never been to the monastery before, which one is the abbot? And that's part of Buddhism. There's no hierarchy. But there was a natural tendency for the enlightened ones to be the ones who would solve all those questions. And basically that got up the nose of the ordinary monks 100 years after the time of the Buddha. Because what happened and this is the history of why Buddhism started to split up into different sects. I don't like sects. You got that? Okay, good. I won't need to explain it now. I'm celibate, but I was meeting sects. But what actually happened was there was the age old controversy in monasticism. The same thing happened to the Franciscans in the Catholic order. We start off being very pure, not having money. After 100 years, some of the monks said, well, it was all right at the time of the Buddha, but these are modern times. I'm talking about 2400 years ago. So the 2500 years ago, things have changed, they said. And this is actually recorded history. And it's great actually, to see in the past as people still get the same old arguments as they do today, that it's not practical. These days. You're going to be a modern monk 2500 years ago. They're saying, we've got to keep money now. And the old monk said, no, you can't is against the rules. Now we've got to change those rules. No you can't. And so there's a big controversy. It became what became known as the Second Council of Buddhism. And at that second Council they try and have some sort of votes, but they couldn't agree. In our laws we cannot go any further analysis. Unanimity majority doesn't work because we realize that the minority will not be happy. Everyone eventually has to agree on a solution, has to be in unanimity in monastic rules. So they couldn't agree. And so they decided, let's allow the enlightened ones to decide. So the enlightened ones decide, no, you can't have money. And that was the end of it. And all the other ones the ordinary. So don't blow monks. They weren't happy. And especially for those students of history. This happened in the town of Wesley, just north of Patna, north of the Ganges, in the heart of ancient Indian democracy. This was a democratic republic for those who think democracy started in Greece, you don't know your history. There was a parallel democracies, very vibrant, long standing and successful in India. In the time of the Buddha. They were so well-established already, they had to go back much earlier in history. But we cannot find out how long. Democracy was not a Greek idea. It was parallel, uh, introduction, both in the Indian subcontinent and also in that part of Europe. This was a democracy. And elites decided now after that time, what happened. And this is history. The people who lost their argument, the ordinary monks, they started to get upset about the authority of the abacus. From that time on, you started to see people say that our hearts, well, then they may be, uh, perfect in their understanding of dharma, but they're not always perfect and worldly things. They can make mistakes. This is actually where you start to see the denigration of the arhat putting them in their place. And at the same time, we started to see in history of Buddhism, the rise of an alternative to the arhat. Instead of becoming an enlightened one, become the Bodhisattva, the one who's on the path to become enlightened. But who puts off that final enlightenment for the sake of all other beings? And this is actually where the Bodhisattva starts to rise in the history of Buddhism. But there was also another movement as well, because to be an advocate was a bit hard. You know how you have to give up everything can you can't sort of do this and you can't do that. And sometimes when you're in a position of authority, they might come and ask you, Ajay and Brahma, you and Aroha, because we've heard the monastery down the road over there, there are huts. And so there's always this peer pressure. And that would also have been there at the time. It's nature and obviously that sometimes it was just a bit too hard to actually to fulfill the goal. And so we also there was a lot to be gained in having another goal saying, well, you know, men are being our hut, but I'm a Buddhist. And the requirements for the bodhisattvas were much less for being the other hut. So that also was a popularization. So at that time, you can see about 3 or 4 centuries after the time of the Buddha, there's a whole new set of scriptures started to appear. And we have the start of the Mahayana tradition. Now. That's actually how it started. There was a history there. And that history is important because it gives some understanding of where it came from. But you also have to understand what it means. Once you started getting it split off between the Bodhisattva and the arrow hut. I should also mention that these were mostly sort of people who wrote the books, made this separation, because that's the only reference we have in the books. And I've always noticed the ones who write the books are usually not the ones who do the practice. If you can't do it, you usually write about it. And that's why many of the books, as soon as I see these, I think, my goodness, did the fellow really know what they're talking about? Why do they do this in the first place? Now, I say that with a bit of a a, uh um a caveat, because I've written a couple of books. So it's not always the case that people are looking for books. But I've always a bit untrustworthy of books. And you know that story which I heard when from a Zen mind? Can I think this is a great story that anyone who writes a book has to spend the next seven lifetimes as a donkey. There's the comic result of that. Fortunately, I looked through all of the terrible suitors. I couldn't find it anywhere. So I think I'm okay. But there is a point to that as a meaning to that. That sometimes the books can mislead if we just take the books to be the whole thing. So we do actually get a split, which happened 2 or 3 centuries after the time of the Buddha, into different schools, mostly because of people to thinking too much, writing books and arguing and not actually doing the practice. Because even then it's quite clear from the evidence of that time that most of the monks, they didn't, if you don't mind me saying this, didn't give a damn what particular type of Buddhism you were, what particular type of school you were, because there was so much in common. They did the practice, they meditated, they penetrated the Dharma, became enlightened advocates and the enlightened ones. They had nothing to do with all of this. However, it all came down to us because after the, uh, Muslim invasions of India, when Buddhism got fragmented, some Buddhists went over to Tibet and then into China. Some went down to Sri Lanka, some went to Java, they went to different parts of the world. And because of their isolation, because of history. These little differences started to solidify into completely different schools. And so we did have a Mahayana, the Chinese Buddhism, the Chan Pure Land, very strong in China, and also the Zen, which was in Japan. We had the the Vajrayana. What we now know is Tibetan Buddhism in not just Tibet, but in Mongolia and even in just the other parts of Central Asia. We had Theravada going down into, uh, Sri Lanka and over into Burma and Thailand and Cambodia. And nowadays, because the world came together, we have all these different traditions all in the same place. Isn't that wonderful? Because when we start to come together, we look at the books, and the books are slightly different, but we look at the practice and the practice is just the same. That's a wonderful thing though. When you start arguing with the scholars, you can argue all day and night and never get anywhere. Whether it should be the bodhisattva is the right way or the aroha is the right way, because some people say that if you just become an arrogant, that selfish, you don't care about anybody else, you're just becoming enlightened for yourself. You should put off your enlightenment for the sake of all other beings and be the last to become enlightened. Which no being cheeky. This is not a putdown Mahayana. But I thought this out many, many years ago because I imagined if I, like other people, put off my enlightenment for the sake of all other beings, I will not become enlightened until the last blade of grass becomes enlightened. That's actually a vow. And I thought, what happened then? Once all the other blades of grass and all the other people and all the other beings become enlightened. All you'd have left with this group of bodhisattvas, all who've made the same vow as I did. And I could see this great traffic jam at the end of time, where I was saying to Manjusri after you. And he said, no, no, no, after you, because I made the vow. Yeah, but so did I. And then there's Guanyin as well, and there's all these other people. Who's going to go first? And of course, that's already being cheeky because that is not already what it means. And it's not and it's not being. And I've seen many people who have their degree of selflessness. I'm not concerned about myself. I'm going to serve other people. Other people become in line before me that degree of selflessness. I know what that leads to. That by itself leads to enlightenment. In the same way that when you know all you people learn meditation from me, when I teach meditation, I say, if you want to get into deep states of mind, you will never be able to. Because it's the one thing which stops. You got to let go. Get out of the way and allow it to happen. Now you can see if you say, I want to become enlightened. I want to get into deep meditation. It can't happen. So you can see that Mahayana mind. I'm going to let go of myself. I don't care what happens to me. That is Theravada practice. That's meditation practice. And say that I have to practice wanting to become enlightened. In other words, wanting to sort of be free, knowing how to be free then. Because being free can help so many other people. You can actually teach from experience what a wonderful thing that is. So in the end, if you really want to be a bodhisattva, if you really want to serve other beings, the best thing to do is become enlightened being arhat. And if you really want to be in our hut, the best he could be is being Bodhisattva. That's the fastest way to being an arrowhead, because that is what I've found. So we have this difference of opinion, which people have, but these are only the scholars. And a lot of times just the scholars who have egos. There was a Tibetan monks some years ago is called Joakim Trungpa. He was a drunkard, but nevertheless he said some very wise things. And one of the wise things he said was this idea of spiritual materialism. At that time, maybe 30 years ago, when materialism was a word which was being coined, he applied it to spiritual materialism. Now, what spiritual materialism materialism is, is just we accumulate our spiritual possessions, our spiritual capital. Now I keep the five precepts. How many precepts do you keep? Only two. Na na na na na. I'm superior than you are. But I do eight precepts. I must be better than you are. But I do ten precepts. I'm a disciple of this. I know I'm a disciple of that bodhisattva. So a lot of times. And I'm not just joking. Sometimes people get into that stuff and I think, you know, you guys are just terrible and you're hopeless. But if you do really, really well and you sort of complete the course under Jim Brown, then you can go to the Tibetan temple and we'll give you the higher teaching. And then why don't you finish the high teaching under the Tibetans? Then you can go to the Zen to get the even higher teaching. And then you go to the higher, higher, higher, and again, all of that sort of stuff. Because maybe because of my Western questioning conditioning that we really just didn't make any sense to me. It wasn't Buddhist to compare yourself to other people and say, I am better than you are. However, that was part of spiritual materialism. And you can actually see that in some of the ancient texts of the scholars and other practitioners who even called their selves Mahayana, which means the greater vehicle. And the opposite of that was that he Nayana, which does not mean small vehicle. That is wrong. Pali it is wrong. Sanskrit Hino means gross, terrible, I mean vile, despicable. That's why I see what it means. I'm actually recently evolved. Obviously, a couple of years ago I just wrote to the Oxford English Dictionary and I put them right and said, like Indiana does not mean small vehicle. And I said, the more the photocopies from the dictionaries. And they agreed. They said, wow, we didn't realize that. Thank you. So I have I'm a contributor to the Oxford English Dictionary. But you see that spiritual materialism again. But nevertheless, that is to sort of get rid of that. And so sometimes that people say, well, actually what are these Yano saying? Indiana Mahayana. What, your honor, is that Jim Brown and you should all know by now I am Haryana. You got it. You got to. That's why you yada yada. You should make it fun. And I noticed doing this just to entertain you. Because when it's fun, a lot of times the reason why people laugh is, is the point in there. And religion should be fun. And it's a waste of time going these cold churches or these these dull sermons or these monasteries or something. Is religion a bad name when it's boring? But to many young people, they don't go to religion because it's boring. You've got to make it fun and there's no reason why it shouldn't be fun. It shouldn't be joyful. I get a lot of joy out of my meditation. I get a lot of happiness out of being a monk. This is not a boring thing to do. It's one of the best things I ever did in my life. Being a monk wouldn't give it away for the world. Now you can see that the happiness and the joy. That's why Haryana is a valid path. And you got Triana and you got this in. And a lot of times, if you hear Adrian Graham come up and say, you know myself, you say this is the best vehicle. Don't go to that temple down the road. Don't go and practice like that. Just practice. My way. This is the only way. That sort of stuff should always make you doubt. That is spiritual materialism. Each one of those paths is valid in the same way that you can go to the different restaurants and get Thai food, Chinese food, McDonald's or whatever else you want to eat. It's all good. It all keeps you going. It's what you do with that. Food is most important. So the point is, what do we do with this? Now this is actually where we stopped just looking at the books. We realize what those books really mean. It is. This is a bit of a tangent, but it's topical because I was reading in the paper last week, there was a huge outcry in the Muslim world because there was an accusation that the copies of the Quran had been flushed down the toilets. What would happen if you flushed down a copy of the Dharma powder down the toilet or the triptych? You know what I'd do if that happened here? I call a plumber. Because that's a practical thing. He'll block out the sewage systems. But would I get upset and angry? Would I start a Buddhist jihad or holy war? And obviously no, because and I mentioned this at a talk I gave some rather recently because you can flush a book down the toilet, but you're not going to flush the principles with that walking bodies down my toilet. I'm not going to allow anybody to flush down peace, forgiveness, love, tolerance that you will not flush down any toilet. You can't unless I allow you to. And if I do that, I'm stupid. So why do we mistake the messenger with the message? The book. They are great books, but they are just the messenger of truth. They're the messenger of peace, the messenger of love, and the messenger of forgiveness. They're the messenger of understanding and peace. So why do we allow these books? Well, what people do to our books or to our image is to destroy what those images are really there to point to. So you all know when the Taliban destroyed those big Buddha statues in Bamiyan. I was so proud of the Buddhists for saying I. Never mind. So you can destroy the Buddha statues, but you'll never destroy our peace and forgiveness, our sense of harmony and our sense of friendliness to you. You can destroy all the Buddha statues you like, but you won't destroy Buddhism. You want to destroy the message which that Buddha statue is embodying the sense of peace and forgiveness. Truth, harmony. That's what's really important. Isn't that what the books are there for? So what is the message of Theravada, of Mahayana Zen or whatever? They've all got these great messages. The great thing about Mahayana was it made us compassion to so prominent and sometimes into a vada that was always there, but sometimes it could be forgotten because it was not prominent. So thank you for Mahayana for actually making such a compassion so important. Theravada. Sometimes the Mahayana they lost, you know, the idea of like a strong virtue and and a commitment to the practice of meditation and and, uh, simplicity. Oh, thanks for Terra Vada, for having all these simple, direct teachings. It's great to have there. Thanks for Zen for having this one. Focus on meditation. Meditation. Meditation is hardly anything else in Zen, the meditation. Thanks for reminding us of that. Thanks for Vajrayana. They do. I think now they do the whole lot. Especially the great example of the Dalai Lama. Just forgiveness lost his country, but gain the world. So all of these have all got things to offer to this beautiful Buddhism. So we don't compare who's the best. We just use all of this. And once you really get into. This Buddhism business you find. And this is why standard answer in Greece, when people say, what is the difference between Vajrayana? There's Tibetan Buddhism, Zen Buddhism or Japan pure and Buddhism with China or Chan Buddhism of China or Theravada Buddhism, the forest tradition, Sri Lankan Buddhism, Burmese Buddhism we pass on or whatever else, all these different types of Buddhism. I hope I got most of them the same look that different types of cake. They have different icings. That's all. Underneath you've got the same cake, the Buddha cake. The icing is different, the rituals are different. Some of the ways of approaching the teachings are different. But when you follow those teachings, you find out what's going on inside. It's beautiful to see that all the same. Now that tomorrow I'm going off to, uh, Sydney and then to Melbourne vs I'm going to Sydney where I'm doing a joint race celebration. Just like last week. We did our waisake here. That was basically for for our group the week before. Many of you know that I participated in No Way Sex ceremony in Supreme Court Gardens, run by the Taiwanese Mahayana group in Guildford Road in Melbourne's. And it's very nice that I was there in the front seat. Sister William was there also in the front seat. And we're supposed to know if you look at the books, we're supposed to be enemies now with Theravada. Mahayana. But look, the truth of the matter is, when we work together in a seamless way and as I say, and the reason why I'm going to Sydney to a joint way sex celebration got all the different Buddhist groups are going to be there. And I'm going to give one of the main speech there, which I'm very delighted to be able to have the honour to do, and then going to Melbourne to do some more, sort of put his stuff. So when I go travelling like this, please don't think that you're taking I'm being taken away from the Buddhist Society of Western Australia because I get a huge amounts of stories and more materials and new jokes for you. It's called research. But also. But also you get great opportunity to widen your contacts. And last year I went to Japan for some ceremony again at a this is a pure land temple. And so after the sermon was finished, it put me up in this hotel and I had this delegation of monks from Germany, and I've heard of one of the monks before. So they all came into my room and had this incredible good discussion, because there were some very, um, great, um, German born Tibetan monks. One of the lamas there is I really sort of respect him very highly. And we ended up talking about meditation. Now, the really deep stuff, the sort of stuff we can't talk with in public about. And we had this amazing discussion which went on, I don't know how long into the night about, you know, what's your meditation night? What's your meditation night? And we found that we came from completely different traditions, but all doing the same thing And that was actually just amazing. Just to see we had these different words. But when you actually explain what those words are from experience, where I know what you're talking about, I call it differently. What you really found there was when you get to practitioners, people who are not just writing the books, but people who are doing it, who actually keeping those precepts. So actually spending years in meditation, our upon our training, the mind getting deep, seeing what the Buddhists saw and how you can see, my goodness, there is no difference. The difference is just on the surface. And see, icing on the cake could be strawberry icing. There can be chocolate icing. You'll be vanilla icing. I mean, I like chocolate. Tibetans like raspberry actually. Worse these than gray. What's that? That's vanilla with a bit of. I don't know anyway. But you understand what I'm talking about. It's just different. So you go inside, you find it is the same. And I recently gave this talk in Singapore on the a conference which we call bridging the traditions. And I said, look, doesn't matter if you call yourself a Buddhist sat for you on the aroha path or what you're actually doing, what what actually is you're doing, not why you're doing it. But what are you doing? And for traditional Buddhists, if you are on a bodhisattvas path, this is the Mahayana, which is no Gratiano is a part as a first part of Mahayana. So they say, if you're doing the bodhisattva practice, you're supposed to be following six parameters, six spiritual practices, and those six spiritual practices. I'm going to rearrange them from the normal order because I'm making a point here. The first three in my order is Dhana Kanti Waimea, which is done with generosity. Kanti is patience, Vidya is energy, and the next ones are precepts or morality. Sila, samadhi, meditation and wisdom Punya. Those are the six parameters, the six practices of the Bodhisattva in the ancient books. Generosity, patience and energy plus sila, samadhi, punya, morality, meditation and wisdom. So what do people on the path toward a Buddhist do? They do generosity based energy, precepts, meditation and wisdom. So they do exactly the same. Why are you doing that? No, the purpose of it may be different. You may think I'm doing this to get, you know, to be able to help other people. Or you may think of it, I am doing this to become enlightened myself, to go to my own problems. But if you look at it, it's exactly the same. And I'll tell you why it's the same is because we have this dichotomy, this dualism in the spiritual world, this dualism. I mentioned this a couple of weeks ago, but it's a powerful point. I'm going to reinforce it now. There are some people who go into the extreme, which is being concerned about themselves and coming here to get rid of your problems, coming here to get more peace in your life even just to lower your blood pressure coming here, you know, for your own benefit, maybe. Now, some of you may think you're coming here for that, but some other people are coming in here to serve for the sake of others. You got the committee members, people like Saul, who's very, very busy just finishing some exams and still comes along here to serve today. The people on the desk over there doing the reception, the people who just actually served you with some snacks they came here to give. They're not really concerned about themselves, a concern about others, which is the right path. I mentioned yesterday are a couple of weeks ago. The both along. There. If you just focus on yourself, you'll miss the path. If you just you just get dull. You just don't get any inspiration. You can't make any progress. I instilled in some monks in my monastery, not actually not in my monastery anymore. But I was talking to a monk today on the phone who still thinks that they can get into deep meditation just by staying by themselves, not giving them any talks, not serving other people. It's amazing. You just. You can't do it. You haven't got the oomph, the energy I've found in my own practice of over the years, almost by default, I've had to serve as a terawatt, a monk. You know, I had the wish just to be a hermit. That's what I like to do. That's my inclination. And people who knew me in my early life as a monk knew I just was spent most of my time just in my heart. Even I did that six month retreat. That's where I feel at home, and I thought I was doing well. For those of you who know the history of the Buddhist society, I came here as number two monk. There was another monk at John Jack Rose young, very good teacher, and I thought, great, I'd be to slimming him for the rest of my life. What a wonderful opportunity just to be by myself. And then he went and disrobed, and all my plans went down the gurgler. So you had to serve. But one thing I found when I was serving my meditation got really good. When I started serving. In fact, I found that, yeah, this actually something personally beneficial to being selfless. If you just think about yourself, your meditation, your wisdom, your spiritual oomph doesn't grow. But also there are some people who just serve others. They give, give, give, give and they don't get anywhere either. And seriously, burnout. They just get frustrated, disappointed, dispirited in the end. They start off with inspiration and they end with inspiration. Which obviously happens after inspiration. You expire. And so people I serve, serve, serve. And then you don't see them anymore. They serve in our Buddhist society committee for 1 or 2 years and then bye bye. Where are they going? I never see him again. Now, both are wrong. The Dharma, the truth is, you won't see that if you focus on the other person and what their needs are. Just by giving. You will never grow. Just by thinking of yourself, you'll never grow. The Buddha taught a middle path. It's not looking at the other person, nor is it looking at yourself. It's looking at the space between you. What's between you and the other person? That is where the Dhamma is seen. That is where growth happens. So the idea of being an altruist, putting off one's own in line with the sake of all other beings, thinking of other beings that never works. Thinking of yourself. Just me that never works. It's what is between us. That is what works. The relationship problem. It's not me. It's not you. It's us And the same way that a person becomes enlightened. The same way they walk this dharma. And I see this down there. If it's just being selfless and doing service, if it's just being selfish, there's another alternative was between us. Looking at the relationship which you have with the world, the relationship which you have with yourself, the relationship you have with life. It's not the other person is not me. It's not the world. It's what we make of it. What's between us and there? You can see why the idea of selfish practice or not worrying about yourself, other people practice is still both miss the girl. So people who say they're Mahayana or Helion or whatever or whatever, they missed it, they'll never get enlightened. In the same way, when you are watching your breath or in the present moment, it's not being in the present moment or not being in the present moment, which is the problem, but having the breath in mind and not having the breath in mind, having these beautiful limiters and deep meditations, beautiful lights in the mind. That is not the point is how you are experiencing those limiters, what's between you and that limiter where there's peace there, whether there's letting go there, whether this. Acceptance there. The door of my heart always opened here. Whatever it is, come in. That selflessness, that matter. That emptiness, that space. That embracing, that is not in the other person, nor is it in you, is what is between us now that transcends Mahayana saying what we are to tell about all these other journeys, because that is where the practice lies. That is actually where we penetrate the truth of things, because life is relationship. We make objects out of these things. Just like we make words to describe our world. We make books to encapsulate those words, and then we fight about the books, and we get upset when a book gets destroyed or flushed down a toilet. How much do we miss things As a muslim, we shouldn't be concerned about Islam. I should be concerned about converting others. It's what's between you and the other is what's important is our relationships. Being a Buddhist or being a Christian, that's not the point is how Buddhists relate to Christians, how Christians and Buddhists was between them. That's the point. Now, can you understand just how true religion, true understanding of all this has to create peace and harmony and stillness in this world? It has to solve the problems because it's not. You aren't the problem, I am not. The problem is how we relate to each other and that will always be the problem. You can't get everybody to be like you. You can't have yourself being like other people. Isn't it wonderful that we're not the same? Remember that wonderful scene from The Life of Brian when Brian is asked to actually to say something profound and on his balcony, thinking quickly and said. You are all different. And somebody put your hand up and said, I'm not. But anyhow, so once we understand what this real dummy is, we can understand it has to be something real truth's real religion. Real spirituality has to be something which doesn't create arguments in this world. And that's I think he died saying of the Buddha who said, you can understand what dharma, what truth really is by its effect. If it does create turmoil, it does create violence, it does create disharmony, lack of peace. So it can't be done. It's not my teachings, said the Buddha. But if it's something which creates peace and harmony and freedom, he said, now that's the teachings of a Buddha. That's Dharma, that's truth. So if it's Theravada which says I am better than you are, this is the original teaching. How do you do my way? Does that create peace and harmony in the world? Of course it doesn't. So it can't be the teachings of a Buddha. If I say that, oh, this is not a good vehicle, you should go to another vehicle. And self-deprecation. That too is not dumb. When we have this beautiful way of relating, relating to other religions, relating to other sects in Buddhism, relating to ourselves, relating to our meditation, relating to our body and its sickness and final death. It's not death is not the problem. If it were, we are stuck because we're all going to die. It's not. Cancer is not. The problem is how we relate to that. Cancer was between us and that sickness was between us and the death. Was between us and life. Now that's where the dam is. And once we can work on that. That was a message in the books. There was a teaching of a Buddha that was actually the message of, I would understand about Jesus or Prophet Mohammed or anybody like peace in this world, and that peace is never going to be attained by just thinking of yourself or worrying about others, but looking at what's between us. It's the relationship which is important. And this is the trouble with even marriages. When you think of yourself, what I need, what I have to get out of this relationship. You know, my requirements are these relationships are going to break if you just selfless and just think about the other person, what can I do for him? What can I give him? What can I do for her? He's going to break down this. What's between you? How you relate together. That's where the partnership happens So this dharma, which the Buddha taught, not only is it for enlightenment, for seeing the deeper truths, it also makes for a happy life as a married couple. And it makes my life simple as well. When you don't come up to me and say, oh damn, Bob, can you please help me? My husband is doing this and my daughter is doing that. Someone's doing this, and that's why I give these talks. Let's somehow stop you ringing me up in the middle of the night. Because sometimes we should never publish our telephone number. Otherwise dial amount happens again. But is that anyhow? So that is the difference between these different traditions. I mentioned historical. I mentioned this. You know what sometimes people say they are? That we're the great vehicle. You're the small vehicle and that's rubbish. There's only what you only talk one vehicle. And it's not that. Sometimes people will say that in the time of the Buddha, people weren't really intelligent enough to understand the real teachings. So they'll put aside in the Niagara and the realm of the dragons until wise people came up in the world. That stinks. Basically doesn't make any sense to me. One of the great things about being a Westerner, you can question and you allow to question, and you're allowed to use reason. You're allowed to use historical analysis, fortunately. After the, uh, Western Enlightenment, when people started questioning the Christian teachings, they started looking at those wholesome teachings and using reason science to find out when those things were written. You can do that with Buddhist teachings as well, because language changes. If you heard a talk and even a Buddhist talk again, look in the old Buddhist book more than 50 years ago, there are words in there you never hear today, and the words today you never heard 50 years ago. Language changes, vocabulary changes. And you can look at an old book and you can pretty much tell when it was written, you know, within 20, 30 years, just because the language, the metaphors, the style, the fashion, this actually what they use actually to try and um, to date the various strands in the Christian Bible when they're actually written and very, very powerful evidence. You can do the same with Buddhist teachings as you see. Does which ones were later? Which ones were earlier? So it was great to be able to have that Western education where you could question and you could penetrate and get rid of a lot of the rubbish. But in the end, when you got rid of all the rubbish, what you were left with these beautiful teachings of a Buddha which are not owned by any set, which no one has a franchise on truth, no one can patent it and say it's mine. If you want it, you have to listen to me. The great thing about truth, it's like the air is there to be breathed in by any being, at any time, in any place. It's why the Buddha said Buddha's only pointed away the book's only point. No way. The different traditions they just encapsulating because of their history. They've emphasized different parts of the way. And if you go into the heart of them, they all carry the full teachings of a Buddha. And those teachings are just the pointers for you to see these things for yourself. So all those different journeys, all those different traditions. It's all for you to use, but you get your meditation together as well. So with those two, the teachings of all the great traditions are just enough sample of it to get an understanding of what it's all about. And meditate. Get your mind very still. You put the two together and you understand what the Buddha was talking about. You understand the Mahayana, the terra vada, the Zen, the water, you know, the whole lot. And you understand, are you? Same cake, different icing, because you've got to the heart of it and it's wonderful and beautiful. You can do that because it means, at least in our tradition, we don't have any arguments. We're not trying to look like the Catholics trying to get the Anglicans to join the Anglicans trying to convert the Catholics. It's nice having a different cake every day and always having the same icing. Variety is the spice of religion. So that's the talk this evening on the different Buddhist traditions and what they mean, and how we can make use of this and what's between us. That is dumb. So thank you for listening today. Okay. Any questions, comments or complaints today? Have I offended anybody? No. Ah, yeah. Okay. The Dharma is the living stream. Yes. Living in the sense you got the. The point is is by living, it's just it's just is always is. Always will be. I went to one of the Buddhist sayings. Even if Buddhas arise in a world or they don't arise in the world, the dumb is always there. If there's a teacher is not a teacher. Her truth is truth is truth always there to be seen and no one owns the truth. That's why the. One of the biggest problems in our world. When religions or organizations come up and say, we have the only truth, or you other guys, girls have got it wrong. And it's much and it's obviously much better for our planet if we can say that this is our version of the truth. This is our explanation, our take on it, our encapsulation. This is how we describe it. But this is just descriptions. The descriptions are different, but we're pointing to the same thing. And that same thing is not a god. That's just another word. It's not like a dharma with an R or dharma with a double M. That's just words. It's actually what is underneath that, what is between us and that idea. If You. That's right. You're asking. So when the Buddha wrote his dharma. And when again, I never wrote a thing, I. Changsha. That's why he will never get reborn as a donkey. And as other people. And actually, I know some of the monks about those books. And they don't want to disrobe because they won't meditate and are spending all their time translating. And that's true. But anyhow, so they they wrote down those things, and that's his explanation. That's his description of the same thing. And so we don't argue about who is right and who is wrong. If you argue then you are wrong. If you're friends, then you are right. Okay. So thank you for coming today. And I will be here next week. And when I come back from Sydney and Melbourne and Canberra. So I hope to see you next week. But the next week is a long time. There is some messages for even what's going to happen tomorrow and on Sunday. So take it away. So.